Trump v. Mazars

Can the House committees get Trump’s financial information from third parties?

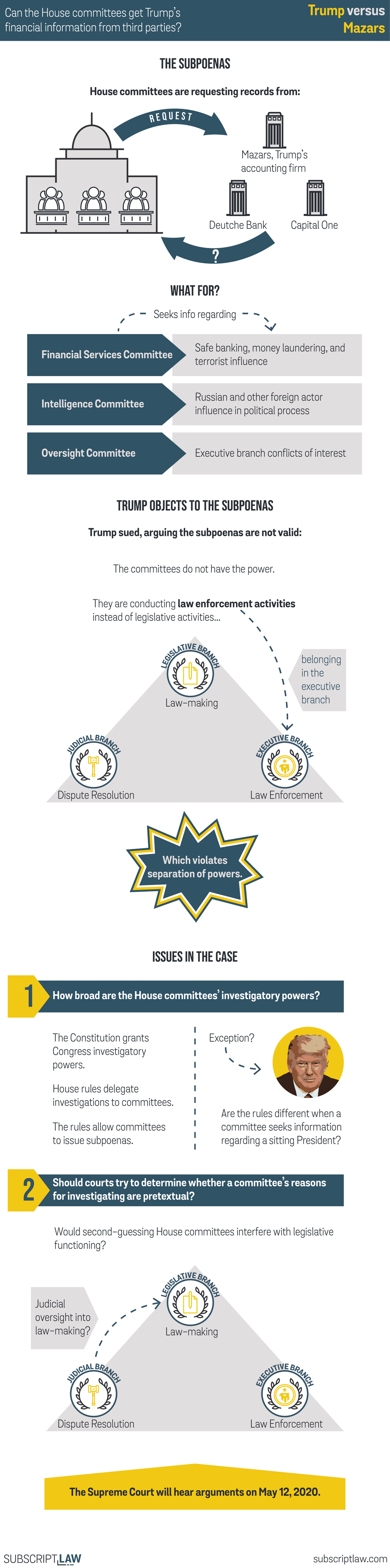

On Monday President Trump will ask the Supreme Court to keep his financial records out of the hands of three investigatory committees in the U.S. House of Representatives. The committees have issued subpoenas to third parties seeking business and tax records related to Trump and the Trump Organization. The President argues the House committees do not have the power to subpoena the records of a sitting President. He appeals after unfavorable decisions in the courts below.

The subpoenas

In 2019, three House committees subpoenaed business and tax records related to President Trump and the Trump Organization. The Committee on Oversight and Reform issued a subpoena to Mazars USA LLP, President Trump’s accounting firm. The Financial Services Committee and the Intelligence Committee subpoenaed records from Deutsche Bank and Capital One, which have had extensive financial dealings with President Trump and his businesses.

The Committee on Oversight and Reform oversees government operations, including the Executive Office of the President and the government ethics laws that require officials and political candidates file financial disclosure reports. The Financial Services Committee oversees the country's banking laws, including anti-money-laundering laws. The Intelligence Committee has jurisdiction over the American intelligence community and can investigate persons who may pose a threat to national security.

In 2019, the House also passed Resolution 507 to clarify that the committees were empowered to obtain records related to the President, his business entities and organizations.

Mazars, Deutsche Bank and Capital One have indicated that they will comply with the subpoenas if the courts declare them valid.

Purposes of the subpoenas

The Oversight Committee heard testimony from former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen that President Trump and Mazars would routinely falsify his assets to get loans and avoid taxes. The Office of Government Ethics also found President Trump omitted payments to Cohen in a 2018 disclosure report. The Committee chairman stated the Mazars subpoena was needed to determine whether President Trump engaged in illegal conduct, had undisclosed conflicts of interest, or was violating the Constitution’s Emoluments Clauses.

The Financial Services Committee’s investigation focused on whether illicit money, including from Russian oligarchs, has flowed into the United States through shell companies and into American investments such as luxury high-end real estate. Deutsche Bank and Capital One have had significant dealings with the Trump Organization and have been fined by regulators for not complying with federal anti-money-laundering programs. Deutsche Bank has reportedly extended President Trump and his businesses more than $2 billion in loans despite a high risk of default. Capital One provided funding for the Trump International Hotel in Washington, D.C.

The Intelligence Committee’s investigation concerns Russian and other foreign efforts to influence American elections. The Committee is trying to determine if foreign actors have financial leverage over President Trump or his businesses, if the President or his family are at risk of foreign exploitation or manipulation, and whether the Russian government coordinated with the Trump campaign or administration.

Trump objects to the subpoenas

President Trump sued to stop Mazars, Deutsche Bank and Capital One Bank from complying with the subpoenas. President Trump claims the committees have exceeded their constitutional powers to investigate because the subpoenas do not have valid legislative purposes. Rather, they were issued in an effort to collect Trump’s personal information for political advantage. Trump argues the investigations are improper because Congress is searching for inaccuracies and legal violations in financial statements he filed as a private citizen. Such an investigation is a law enforcement role reserved to the executive and judicial branches. It is meant to expose information for the mere sake of exposure. As such, the records cannot lead to legislation and therefore have no legitimate legislative purpose.

Rulings below

Trump’s arguments failed in the courts below. Both the federal district court in Washington and the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled against President Trump. Trump now appeals to the Supreme Court to determine whether the subpoenas are a valid exercise of the House committees’ power.

The Supreme Court will address several key issues to determine whether the third parties must comply with the subpoenas issued by House committees.

How broad are the committees’ investigatory powers?

American colonists and the Founders saw their legislatures and Congress as having the same sweeping powers of investigation as the British Parliament. In 1791, Justice James Wilson said, “The house of representatives . . . form [sic] the grand inquest of the state. They will diligently inquire into grievances, arising both from men and things.”

Until the late 19th century, the courts did not interfere with or curtail the investigatory powers of Congress. In 1880, the Supreme Court decided Kilbourn v. Thompson, where a witness challenged a congressional subpoena concerning failedinvestments made by the Navy Secretary. The Court found that Congress had limited powers to compel witnesses, did not have a general power to inquire into a person’s private affairs as courts did, and that the matter was already before a federal court. The Court also held the investigation could not result in valid legislation. Although other cases have clarified and limited the reach of Kilbourn, the holding became the basis for most of the Supreme Court’s limitations on congressional investigations.

The Supreme Court requires that a congressional investigation have a “legitimate legislative purpose,” often meaning information that will lead to legislation. In the 1950s, Quinn v. U.S. and Watkins v. U.S. held that Congress may not exercise “law enforcement” powers. In addition, Watkins held there is no congressional power to “expose for the sake of exposure,” where the predominant result can only be an invasion of the private rights of individuals.

Should courts try to determine whether the committees’ reasons are pretextual?

President Trump argues that Congress’ motives are not legislative, but political. He wants the Supreme Court to look behind the House committees’ stated reasons for the subpoenas to determine that the committees issued the subpoenas just “for the sake of exposure.”

However, legal precedent requires courts be highly deferential to Congress’ judgement. Generally, courts should presume Congress is acting within its legitimate constitutional powers and responsibilities. Courts must also presume that the congressional committees will responsibly exercise their powers by giving due regard for the rights of witnesses.

Given that each of the committees in this case had facially valid legislative purposes for the subpoenas, it is highly unlikely the Court will give weight to President Trump’s contention that Congress' true motive was political. The courts, however, can consider evidence such a member statements or hearing questions to decide whether Congress exceeded its authority.

Are the House committees improperly engaged in “law enforcement”?

President Trump argues that the House committees do not have the power to issue the subpoenas because they are actually trying to purse law enforcement activities against the president.

Under our separation of powers, it is the state or federal executive branches that perform law enforcement activities. Under the Constitution, the only “law enforcement” activity tasked to Congress falls under its power of impeachment. Through impeachment, Congress may investigate wrongdoing by government officials. The investigation requires a majority of the House and conviction requires a two-thirds vote of the Senate. A conviction results in punishment: removal from office and restrictions on holding future offices.

President Trump argues the committees are now improperly exercising law enforcement powers because they are investigating potential legal violations and wish to expose alleged wrongdoing. The individual House committees do not have impeachment power alone, so they cannot investigate Trump with the goal of trying to punish him.

Watkins v. U.S., decided during the McCarthy “red scare,” found a subcommittee’s inquiry into a person’s politics and affiliations did not serve a “public purpose,” but was meant to bring the witness public scorn. The Court held (1) there is no congressional power to expose for the sake of exposure, and (2) Congress is not empowered to expose where the predominant result would be an invasion of an individual’s private rights.

This ruling appears at odds with the notion that courts should not be trying to determine a pretext for a congressional investigation. In fact, exposure of wrongdoing is one of the greatest tools at Congress’ disposal. In the words of Justice Louis Brandeis, “Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.”

The House committees point out, in contrast to Trump’s argument, that they cannot be pursuing law enforcement activities against the president because Congress cannot pursue charges against an individual without the executive. If Congress finds evidence of a crime during its investigations, Congress’ ethics committees may refer the cases to federal or state executive authorities. Only through the executive authorities may the government bring cases for possible law violations discovered during investigations.

Amicus argument: The information does not really belong to the President

Professor James Wheaton and I filed amicus briefs in Mazars and Vance supporting the House committees. We argue that President Trump cannot object to Mazars, Deutsche Bank and Capital One turning over the financial information because Trump is legally separate from the entities requested to provide information.

The subpoenas request information held by more than 500 business entities connected to the Trump Organization. President Trump argues that because he has not divested his economic interests in the business entities, or put them into a blind trust, they remain so closely tied to him that the subpoenas must be invalid. President Trump further argues that producing these records would distract him from his official duties.

The amicus brief argues the President is not being asked to produce any records, so compliance with the subpoenas should not take up any of the president’s time. Further, President Trump does not need to consult with any of the entities because he publicly resigned from positions of authority before becoming president. Therefore, the entities are legally separate from the President, and the subpoenaed documents do not belong to him, contrary to Trump’s arguments.

The political question doctrine

An issue that could resolve the case on a technicality is the “political question” doctrine. The Supreme Court has asked the parties and the Solicitor General to brief whether the political question affects this case. The political question doctrine allows the Court to avoid deciding a case on its merits because the lawsuit is a political conflict that should be resolved by the “political branches”: Congress and the President. If the Supreme Court uses this doctrine and does not decide the case on the merits, Mazars, Deutsche Bank and Capital One may see the subpoenas as legally valid and release the financial records to Congress.

Recent Reports:

fromSubscript Law Blog | Subscript Lawhttps://https://ift.tt/2LdG36U

Subscript Law

4 Curtis Terrace Montclair

NJ 07042

(201) 840-8182

https://ift.tt/2oX7jPi

Comments

Post a Comment