Kelly v. United States

Argument: January 14, 2019

Petitioner Brief: Bridget Anne Kelly

Respondent Brief: United States

Decision: TBA

Court below: United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

Christie staffer involved in Bridgegate seeks to avoid criminal prosecution

One of the three NJ officials who took the fall for the 2013 “Bridgegate” scandal is at the Supreme Court this term. She argues she shouldn’t face criminal fraud charges for her actions.

“Bridgegate”

In 2013, three New Jersey officials ordered the closure of two lanes of the George Washington Bridge — the busiest bridge in the world — to get back at the mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey. The mayor had refused to support Chris Christie’s run for governor, and the Christie appointees closed the lanes to cause traffic problems in Fort Lee.

The lane closures took place on the first day of school in September 2013, and the thousands of commuters to New York City were backed up for hours. The traffic was so bad that a group of paramedics were forced to walk from their ambulance to a 911 call.

The bogus traffic study

To order the lane closures, the NJ officials told officials in charge of the bridge that they needed to conduct a traffic study. There was no traffic study. The officials made it up so they could get Port Authority officials (in charge of the bridge lanes) to close the lanes.

Port Authority had to pay for an extra toll collector and for engineers to work on the fake traffic study, adding up to about $5,400.

Bridget Kelly’s role

Bridget Kelly was convicted of criminal fraud charges for her role in the scandal. Kelly worked as the Deputy Chief of Staff in the New Jersey Department of Intergovernmental Affairs. She communicated with two other NJ staffers to create the fake traffic study and order the lane closures. In one email, in response to a suggestion by another staffer (David Wildstein, chief of staff to the deputy executive director of Port Authority) to close the lanes, Kelly replied “Time for some traffic problems in Fort Lee.”

The convictions

Kelly was convicted of two different types of fraud defined by federal law. Both provisions make someone liable for improperly obtaining or misapplying property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses. One of the laws applies to agents of federal fund recipients (which covers most state government employees because states receive federal funds), and the other is broader, covering anyone engaged in wire fraud.

Question in the case

In this case, the issue is whether the provisions’ term “property” includes the type of government resources that Kelly commandeered when she ordered the lanes closed. Are employee labor costs “property”?

Kelly’s position

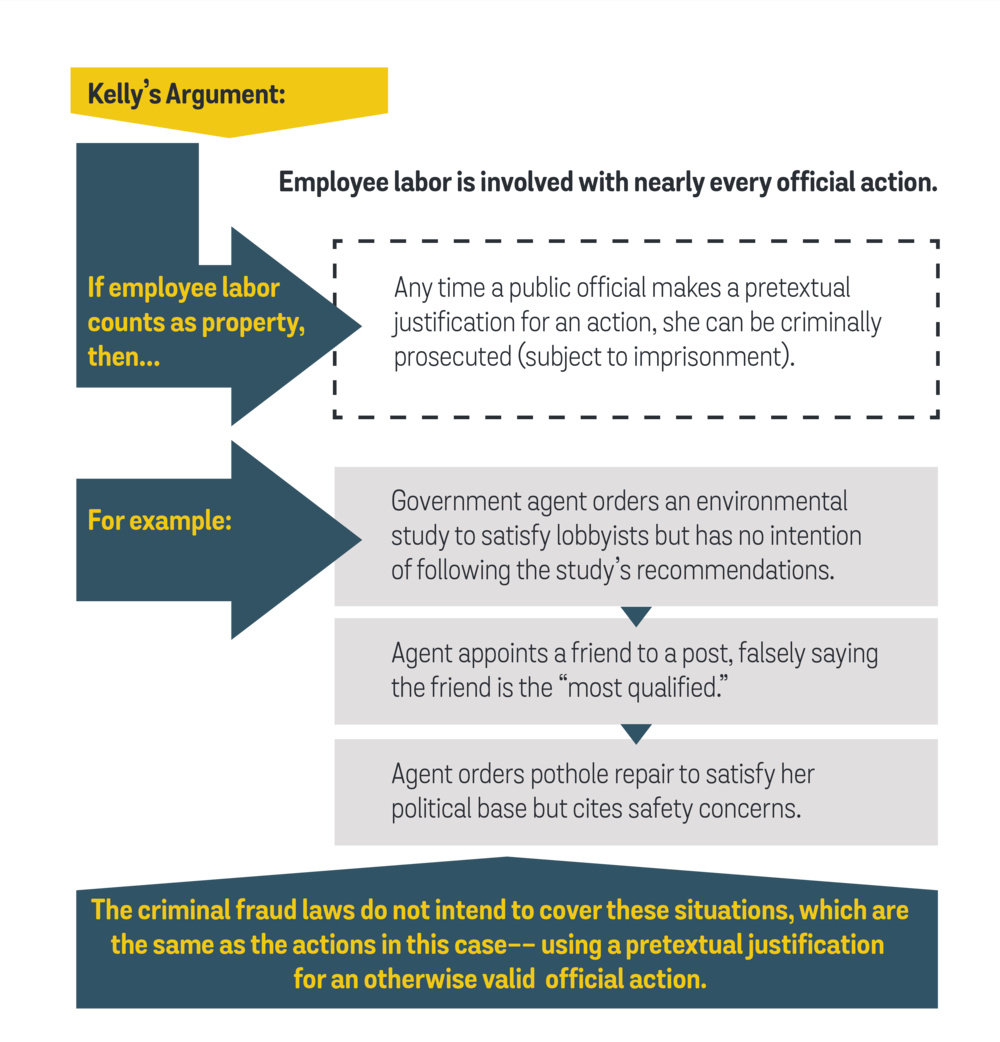

Kelly argues that employee labor costs are not included in the definition of “property” under the federal fraud laws.

Kelly claims employee labor costs cannot be “property” under the criminal fraud laws because that would subject government agents to liability for many actions that clearly we would not consider fraud. Any time a government agent orders an action, employee labor effectuates it.

In Kelly’s view, all she did was make up a false pretense for an otherwise valid official action. She had the authority to order the lane closures, and she just made up a traffic study to get it done. Government agents make up pretextual reasons for their actions all the time (or at least often enough). We can’t expose them to criminal liability — subject to imprisonment — for being politicians.

For example, suppose a government official orders an environmental study because lobbyists are bugging her. But she has no real plans to follow the study’s recommendations. That’s a pretextual rationale for a use of employee labor. In another circumstance, suppose an official appoints a friend to a post. The friend isn’t the most qualified, but the official says so in hiring. Suppose an official orders pothole repair in her constituents’ neighborhood, citing safety concerns but really just trying to please her people. These are all examples of pretextual rationales for otherwise valid official actions. Surely we don’t want to subject all of these officials to criminal liability.

Just last year, Kelly points out in the introduction of her brief, the Supreme Court heard a case in which the Commerce Secretary was accused of making up a pretextual rationalization for putting the citizenship question on the U.S. Census. The Court concluded that the rationale indeed did not fit. And the Justices sent the case back asking the Commerce Secretary to do better. In Kelly’s view, the rule the U.S. is asking for in this case would have imposed criminal liability on the Commerce Secretary - which is obviously not what the Court would intend.

The United States’ position

The United States says Kelly has framed the case all wrong. She didn’t just make up a pretextual reason for an otherwise valid official action. Kelly actually did not have the authority to order the lane closures. She had to lie in order to order them. And in lying, she used government resources. She commandeered them for her own purposes -- completely illegitimate purposes that served only negative public benefit.

Of course employee labor is “property” in the meaning of the fraud laws, the United States says. The government spends money for employee labor. Kelly’s actions imposed a cost and a diversion of “property” for illegitimate purposes. Just as the court below decided, Kelly is criminally responsible.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on January 14, 2020.

Recent Reports:

fromSubscript Law Blog | Subscript Lawhttps://https://ift.tt/37zXhED

Subscript Law

4 Curtis Terrace Montclair

NJ 07042

(201) 840-8182

https://ift.tt/2oX7jPi

Comments

Post a Comment