Kahler v. Kansas

Supreme Court poised to take a deeper look at “insanity” in criminal law

Kraig Kahler faces the death penalty for murdering his wife, his two daughters and his wife’s grandmother. According to the record, Kahler’s issues began with his wife taking a lesbian lover. Kahler initially agreed, in hopes he could be a part of the action, but at some point he got jealous. The wife left him. Unable to handle the mental strain, Kahler killed everyone except his son at a Thanksgiving get-together. Feel free to Google the guy for more about the emotional story.

Having been sentenced to death, Kahler now appears at the Supreme Court arguing Kansas’s criminal law is unconstitutional. Kahler wants to seek relief from the death penalty by way of “insanity.” Psychological reports show Kalher suffering from narcissism, histrionic personality disorder and obsessive compulsions.

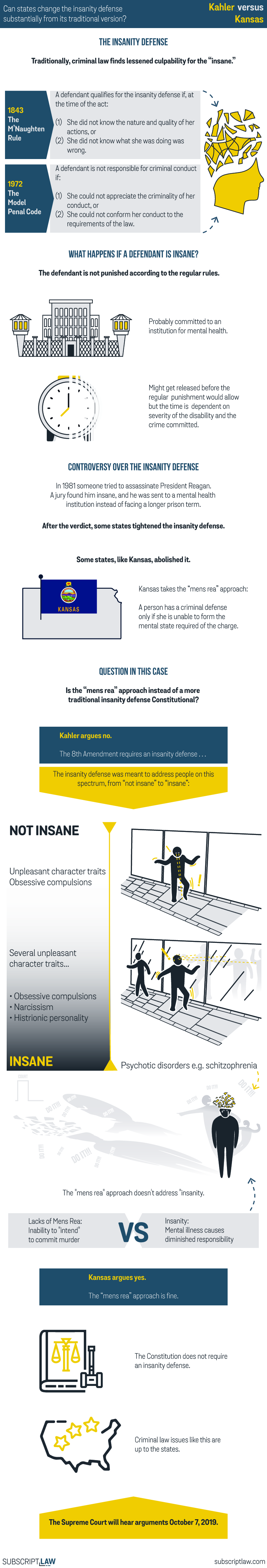

The insanity defense

In many states, Kahler could argue for the “insanity” defense based on his illnesses. Traditionally, someone qualifies as “insane” if he didn’t know the “nature and quality of his actions” or if he didn’t know his actions were wrong (M’Naughten Rule, 1843 England). According to the “insanity defense,” an “insane” person has diminished culpability, and criminal codes with the defense do not punish the insane according to the regular rules. Under this the traditional “insanity defense,” Kahler would argue his mental disorders prevented him from understanding the wrongfulness of his actions.

However Kansas doesn’t allow a traditional “insanity” defense. In the 90’s, Kansas decided it doesn’t want to give murderers a chance to prove they didn’t really “appreciate” the wrongfulness of their actions. Kansas’s rule is narrower. It’s called the “mens rea” approach.

“Mens rea” refers to someone’s guilty state of mind. Only if a person can prove she was so affected by mental illness that she was unable to intend to commit the crime can the person get relief. Someone whose world is so affected by mental illness that she’s walking around in virtual reality swinging swords but not actually thinking she’s murdering anyone can qualify for the “mens rea” approach. Not Kahler, who knew he was killing his family and intended to do so but did it because he’s a deranged narcissist.

Is Kansas’s “mens rea” rule an acceptable replacement of the traditional “insanity” defense? That’s the question in this case.

The Constitution

Although the “insanity” defense has been around for a while in U.S. legal history, the Constitution does not specifically say that the government must provide it. Kahler must argue the requirement to give the insanity defense is elsewhere in the Constitution.

The Eighth Amendment says the government can’t give people “cruel and unusual” punishments. The Constitution also says, more generally, the government can’t take someone’s life or liberty without “due process” of law. Kahler says Kansas’s “mens rea” approach runs afoul of both Constitutional requirements.

Kalher’s view

According to Kahler, the “insanity defense,” which separates people who are morally blameless has been a part of Anglo-American criminal law since the 14th century. People who lack the ability to distinguish between right and wrong lack a necessary quality to deserve punishment: culpability. The “insanity defense” has been a part of legal history in this country, not by chance but by virtue of the purpose of criminal law. Accordingly, the Eighth Amendment’s ban against “cruel and unusual” punishments incorporates that governments must have an insanity defense that goes easy on the morally blameless. Similarly, the insanity defense in incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause.

Our graphic shows how the “insanity defense” intends to pick out people on the spectrum of how morally blameless they are. At one end of the spectrum, there are people with bad character traits that aren’t morally blameless. In fact, they could be normal. At the other end, there are the “insane”: people who are so fundamentally confused as a result of their illnesses that they cannot distinguish between right and wrong. Kahler argues states must have an insanity defense that picks out the morally blameless.

Kansas’s view

Kansas, in return, says there’s nothing in the Constitution that says states must go easy on people who can’t distinguish right and wrong. What Kansas has done, rather, is to make a policy judgment that the people it will go easy on are the ones that are so delusional that they were unable to form the intent for crime. If someone’s reality is so affected by illness that she murdered someone by pulling a gun trigger thinking it was a water gun, she didn’t actually form the intent for murder. Kansas’s “mens rea” approach would grant that defendant a defense. But, Kansas says, the Constitution doesn’t require a state to pick out who is “morally blameless,” in the way of the traditional rule. In fact, Kansas notes, even determining who is “morally blameless” requires a policy call. What is morally blameless? Kansas says it’s people who can’t form the intent for the crime.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on October 7, 2019.

Comments

Post a Comment